RAF 15 Operation Frothblower ~ Plzen 16-17 April 1943 (revised edition)

ROYAL AIR FORCE

76 Squadron RAF Linton-on-Ouse, Yorkshire

Reader. Thank you for visiting. Although this paper rests upon one single squadron, 76 Squadron based at Royal Air Force Linton-on-Ouse in North Yorkshire in April 1943, the research reaches far beyond the Squadron’s original operations log.

Overall, this operation saw the loss of 59 aircraft and their crews. The statistical anaylsis at the end is revealing.

Today, we are used to having explained to us what it takes to have a ceremonial flypast over Buckingham Palace, London. It isan operation of great skill.

Now let us wind back eight decades. In the early evening of 16 April 1943, last light was being taken advantage of. Imagine. Aircraft from 31 squadrons of Royal Air Force Bomber Command covering twelve Counties, assembled in the night sky forming up into the Bomber Stream that would head out and then split into Main Force and Diversionary Force. This was normal. My parents and grandparents were willing to asnwer endless questions. From the six of them I learned many of the wartime sayings… One is apt to this discussion.

Ah! It’s going to be a heavy one tonight!

The exclamation “ah” was invariably pronounced as one syllable but with a rising tail.

SUMMARY OF ATTACK ON PILSEN (16/4/43)

The original Operations Log of 76 Squadron, Ops Room,

relating to Operation Frothblower and Operation Chubb

on 16-17 April 1943,

kindly provided by Mr Michael Harrison,

a Co-Administrator of 76 Squadron Association.

KTW

Transcript

Summary of attack on Pilsen, 16 April 1943

Eleven crews were briefed for operations; ten being detailed to attack PILSEN, and one to attack MANNHEIM. Both attacks were highly successful. The evening was perfect as the aircraft took off and the visibility over both targets was just as good. Over Pilsen, the railway, factory and river could be visually identified and this made it possible for the Bomb Aimer to be very accurate. The defences around the Skoda Works were also helped by this weather and the flak was very accurate. Unfortunately, three of our aircraft failed to return and have since been reported missing. The seven crews which returned from the Pilsen raid reported having dropped their load at an average height of 8,000 feet, and that many H.E. bursts and large fires were observed in and around the target. The other aircraft which attacked a target in MANNHEIM, reported on return to Base that three very large fires were burning in the target area and that the smoke from those fires rose to a great height. Defences over this target were quite moderate.

End of Official Entry

Introduction

THE OPERATIONS ROOM LOG is a contemporaneous record, and I therefore read the 76 Squadron Operations Log in that light.

I imagine the crews safely returning, their desire to get the briefing over with, their need to get their heads down. I pause. They have just flown the longest operational distance of the war to that point. From the northeast coast of Britain, flying across the North Sea, over Occupied Denmark, then a sharp southward leg down into Germany. They split. Main Force carries on into Czechoslovakia. The Diversionary Force continues direct south to Mannheim.

The city of Plzen is attacked. Main Force then turns, They then turns, but this time, by the shortest and most lethal route, straight across the full breadth of Germany, and on still over occupied territory, until they eventually reach the relative safety mid point over the North Sea not far off Norfolk, Lincolnshire and Yorkshire. Eighty years on, I’m aware that the operation was a a complete failure. The 76 Squadron Operations Log informs me otherwise.

Momentarily I ponder. Did the crews just say what intelligence wanted to hear?

But if that be the case, then it is not the Royal Air Force with which I am familiar.

I ponder again.

Their target is the Skoda Works in the city of Pilsen (we know it today as Plzeń). A diversionary attack on Mannheim will draw night fighter defences away from Main Force by way of Denmark.

Then, as now, Plzeń is famed for its Pilsen Lager. In the Cold War it was famous for its Škoda cars that we all used to have a joke about. This was before the old Soviet box morphed to the state of the art Skodas we know of today.

But during the Second World War it had been diverted entirely to armaments. This would not have been with the blessing of the Czech People. They had been occupied as a result of the Agreement between Nazi Germany, Great Britain and France, the outcome of the Munich Crisis 1938, and in which the Czech Government had been excluded from all negotiations.

What have I done?

They had been occupied as a result of the Agreement between Nazi Germany, Great Britain and France, the outcome of the Munich Crisis 1938, and in which the Czech Government had been excluded from all negotiations.

Strange. An angry page of history flutters afresh on the desk. Three years ago Afghanistan’s future was discussed with the Taliban Insurgency without involving the sitting legitimate Afghan Government. And now we look on, not unlike a shrivelled up Neville Chamberlain.

Lesson to be learned?

What the crews report is what the crews have seen in so far as they could tell. That was my initial uncomfortable thought.

I read afresh Peter Wilson Cunliffe’s account of this combined operation A Shaky Do first published in 2007, and available in both print and ebook (Kindle). Notes 1, 3

It is right to report that notwithstanding the original Operations Room Log Entry of 76 Squadron for this attack, the operation, in fact, failed to hit the intended target.

A double-check in A Shaky Do by Peter Cunliffe gave me two very sobering ripostes to the original Operations Log; one by Tom Wingham D.F.C., a bomb-aimer and the other by Harry Hughes D.F.C., D.F.M., AE. a navigator, both serving with 102 Squadron. Note 2

I made a fresh coffee. I walked out into the garden. Looked up at the sky. Beautiful cloud formations after the massive weather front that has just battered the British Isles sweeping in from the Atlantic at between 70-90 mph (112 - 144 km). A silent thought, almost audible. Ken, you know full well that DFCs and DFMs do not shoot the line. They are direct, blunt and to the point as they had to be in battle. I went back in, closed the french doors and returned to the desk. Note 7

“The intelligence report in the squadron records bears no relationship to what we reported. It was a fairly clear night and we navigated on Astro-navigation to the target. Blackie, (The Nav.) and I had every confidence in our astro navigation, and at E.T.A. [we] were surprised to see the P.F.F. marking well to the south of us. Instructions to crews were to only take P.F.F. as [a] guide, but to remain free to make [our] own decision in bombing [the] target. We flew south to investigate when I advised Dave (Pilot) that P.F.F. had made a boob and that Plzeń was further north. We debated whether to call up the rest of the squadron to advise them, but decided against it.

We then turned north to search for the Škoda works and after some time, it was very dark, I identified a river similar to that at Plzeń, where I aimed the bombload, (4 x 1000Ib and 1 x 500 HE). Unfortunately, our photograph showed up as open fields, about 5 miles south of the Škoda works, but I did not bomb the infirmary or whatever it was that the P.F.F. had marked. The raid was a cock-up, no more than up to half a dozen aircraft getting anywhere near Plzeń.”

“I was still new to operations (a sprog), and as a navigator, the most important thing was to know where you were. I knew where I was because the bomb aimer gave me a pinpoint at the river Moselle. We were coned and hit by flak just after this near Saarbrücken and again suffered flak damage near Karlsruhe. Well, we carried on to our next turning point which was to the south of Plzeń, but about seven minutes before my E.T.A the Pathfinder flares went down and [the] bomb aimer Harry Hooper insisted that he could see the Škoda works so we bombed along with everyone else despite my protestations. We landed at [RAF] Harwell [in Oxfordshire, and] we did not get back to base until 13:30 hours the following day having had to repair the flak holes in the ailerons and the tail plane.”

I sat back and thought quietly. My eyes glazed across the names of the 354 men that went down with the 59 aircraft.

A long distant memory recalled the single line oft-repeated in days long gone, the scene almost always going something like this.

I rest my Case, Your Worships.

Thank you Mr. Webb. Pray, be seated.

A silent crisp respectful nod, a glance to my friend in the Prosecution.

Our work was done.

From the Bench in Court One, whispering heads, the Chair leans forward

The Clerk turns and briefly nods.

Turns back and as he stands smartly,

‘All Rise’

The three Magistrates retire. We used to have bets. 2 mins? 5 Mins? 7 mins? before the buzzer sounded to summon the Clerk to Chambers to advise on a point of law… …

I liked the Clerk very much. A solicitor. And years before as a police constable being over-awed by it all as a 19 year old, my father, also a police officer, having quietly expressed the greatest respect for the Clerk, quietly reminding me that he had been a Major in the newly formed Special Operations Executive (SOE was established on the explicit instruction of Winston Churchill) during the War. I learned much from the Clerk in later years, one of the foundation stones of my long legal career.

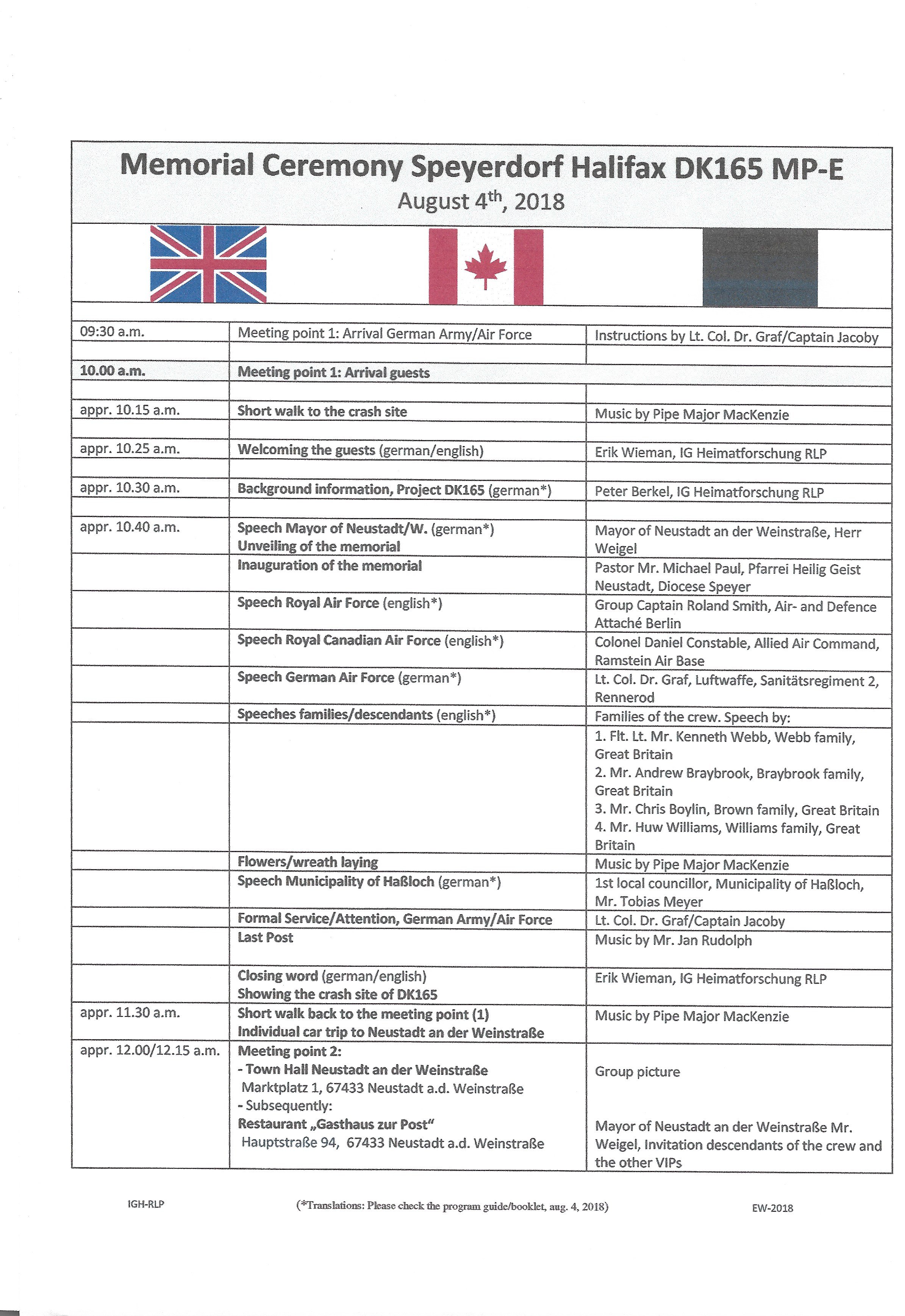

Visit to RAF Linton-on-Ouse 2018

My father’s brother was on one of the eleven crews that flew from RAF Linton-on-Ouse on the evening of Friday, 16 April 1943. A Mk V Halifax on its maiden flight, DK165 MP-E left the runway at 20:41 hours.

On a visit to RAF Linton in 2018, when it was still operational, the nephew of my uncle’s flight engineer Mr J A Braybrook and I were, quite unexpectedly, invited to walk out to the runway.

I am well used to RAF Stations, and seeing again the mighty hangars, seeing the old control tower standing empty, our walking to the runway was an odd, electrifying moment.

We were walking with our host, a wing commander, and I slipped back into military mode … those who have served will know only too well how this happens and without intent. I was chatting to Andrew walking beside me and by a slip of tongue called him Stan. Andrew looks like his uncle, and I admit I used to look like my uncle, but it pulled us both up short. It caught my throat, too.

How strange, to stand on the edge of the runway, to take in the skyline, to imagine a pilot’s eyeline in 1943. Much of the infrastructure around me, stood then in 1943.

We walked over to a single storey block and were invited to look through the windows. A very long table, still in mint condition, use of wear and tear clearly present, still used every day in 2018. Here was where the eleven Crews collected and signed for their parachutes.

Who are these crews?

Who are these men?

What were they doing on the Nation’s collective behalf that resulted in all of us now enjoying 80 years of freedom?

As I do not have access to the full Manifest, only the Chorley Loss Records, I write only in relation to the three crews that are reported missing in the Operations Log.

I have added the Illingworth Crew of 78 Squadron and also the Howarth Crew of 76 Squadron from their night operation against Essen 13 days earlier.

The main image to RAF 15 is of Halifax W7805 MP-M of 76 Squadron being loaded up for an Operation on a target in Essen on 3 April, just thirteen days earlier. I look at the chaps and it helps me to connect to the intense activity in dispersals at Linton on 16 April.

The Price ~ the Ultimate Sacrifice

The Wedderburn Crew

Halifax Mk II DT575 MP-Y Operation Frothblower Plzen Škoda Works Took off 20:49 Linton

Sgt B W E Wedderburn

Sgt J Strachan

Sgt B J Clinging

Sgt F O Ross RCAF

Sgt F C Fidgeon

Sgt L N Jonasson RCAF

Sgt S H C Brown

Chorley Records record that DT575 MP-Y crashed near Liesse (Aisne), 9 miles (15 km) NE of Laon, France. All lie in Liesse Communal Cemetery.

Sgt Jonasson RCAF came from Point Roberts in Washington State and at 17 years of age was amongst the youngest airmen killed on operational duties with Bomber Command in World War 2.

The Wright Crew

Halifax Mk II JB800 MP-U Operation Frothblower Plzen Škoda Works Took off 20:01 Linton

Sgt G G Wright

Sgt A G C Read

P/O H E Smith

P/O A N Cooper

P/O J F Webb

Sgt D B Wombwell

Sgt F A Robb RCAF

Chorley Records record that JB800 MP-U crashed at Mundelsheim some 13.6 miles (22 km) NNE of Stuttgart. Those who died in the crash are buried in Durnbach War Cemetery. Sgt Read and Sgt Wombwell mercifully survived and became prisoners of war.

But the entry goes on to emphasise the magnitude and horror of total war.

On 19 April 1945, Sgt Read was mortally wounded when Allied fighters strafed a prisoner of war column near Gresse. Sgt Read lies in the 1939-1945 War Cemetery at Berlin.

The Illingworth Crew

Halifax Mk II JB870 MP-F Operation Frothblower Plzen Škoda Works Took off 21:15 Linton

Sgt W Illingworth

Sgt R Woodhall

Sgt C G West

P/O H D Dixon

Sgt E G Thomas

Sgt S W Patton

Sgt D A Watkins

Chorley Records record that JB870 MP-F was borrowed by 78 Squadron. The aircraft crashed near Roye (Somme), France, where all seven crew are buried in the New British Cemetery.

Pilot Officer Dixon’s father was the Revd Henry Dixon MA of Manaccan Vicarage, Cornwall. Like his father, Pilot Officer Dixon was also an MA and had graduated from Magdalene College. There appears to be a typographical error in the Chorley Record which refers to Plt Off Dixon also as a sergeant. I have, therefore, used the Manifest.

The Webb Crew

Halifax Mk V DK165 MP-E Operation Frothblower Plzen Škoda Works Took off 20:41 Linton

Sgt K E Webb ‘skipper’

Sgt S Braybrook ‘engineer’ ‘Stan’

Sgt K R G Williams ‘navigator’ ‘Rees’

Sgt J Kay ‘bombardier’ ‘Jacky’

Sgt A R Ross RCAF WOP/AG ‘Rossey’

Sgt L B Mitchell (Mid U Gunner) ‘Mitch’

F/S G Brown Tail-end-Charlie (at 27, Geoff was affectionately ‘grandad’)

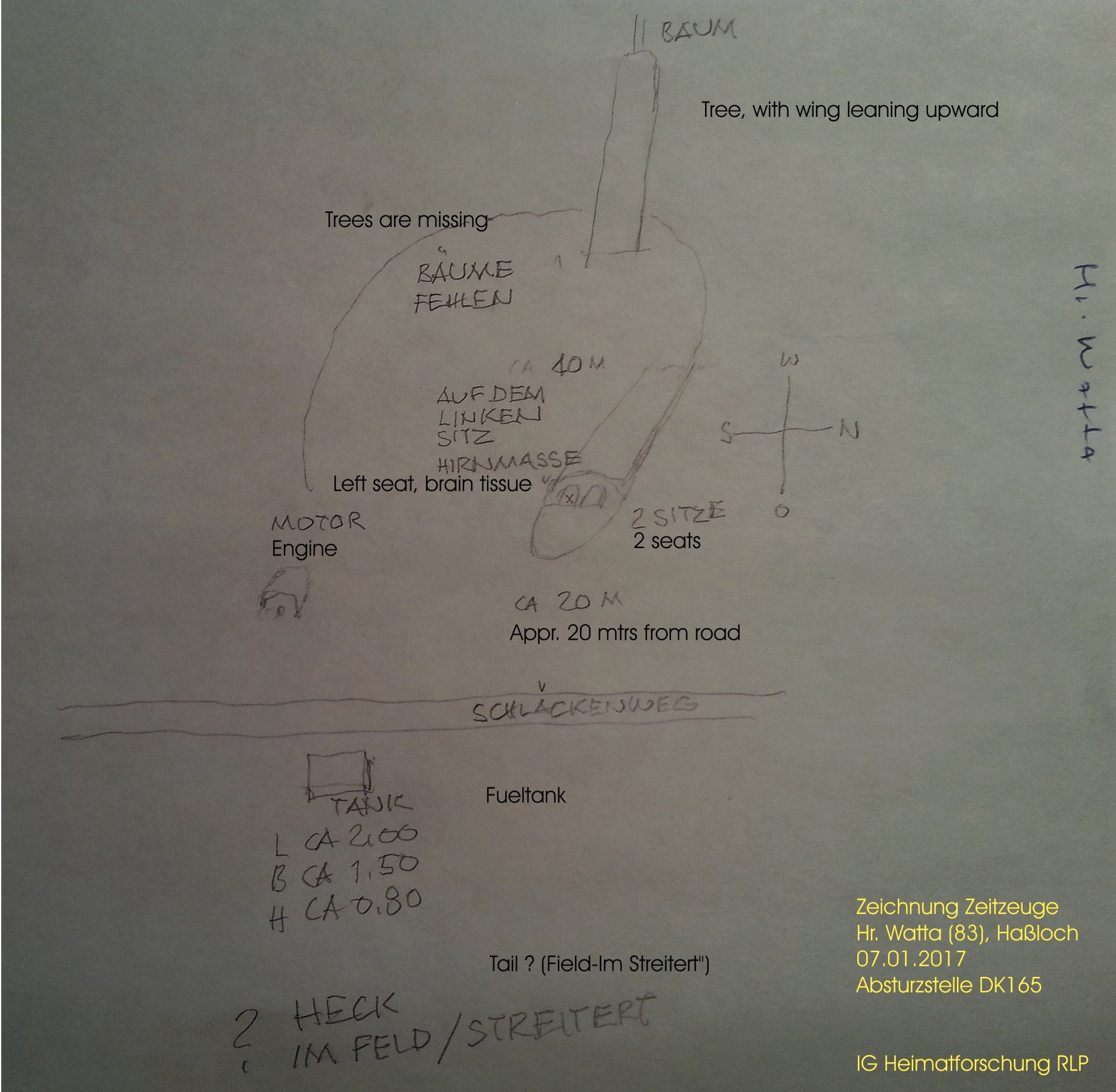

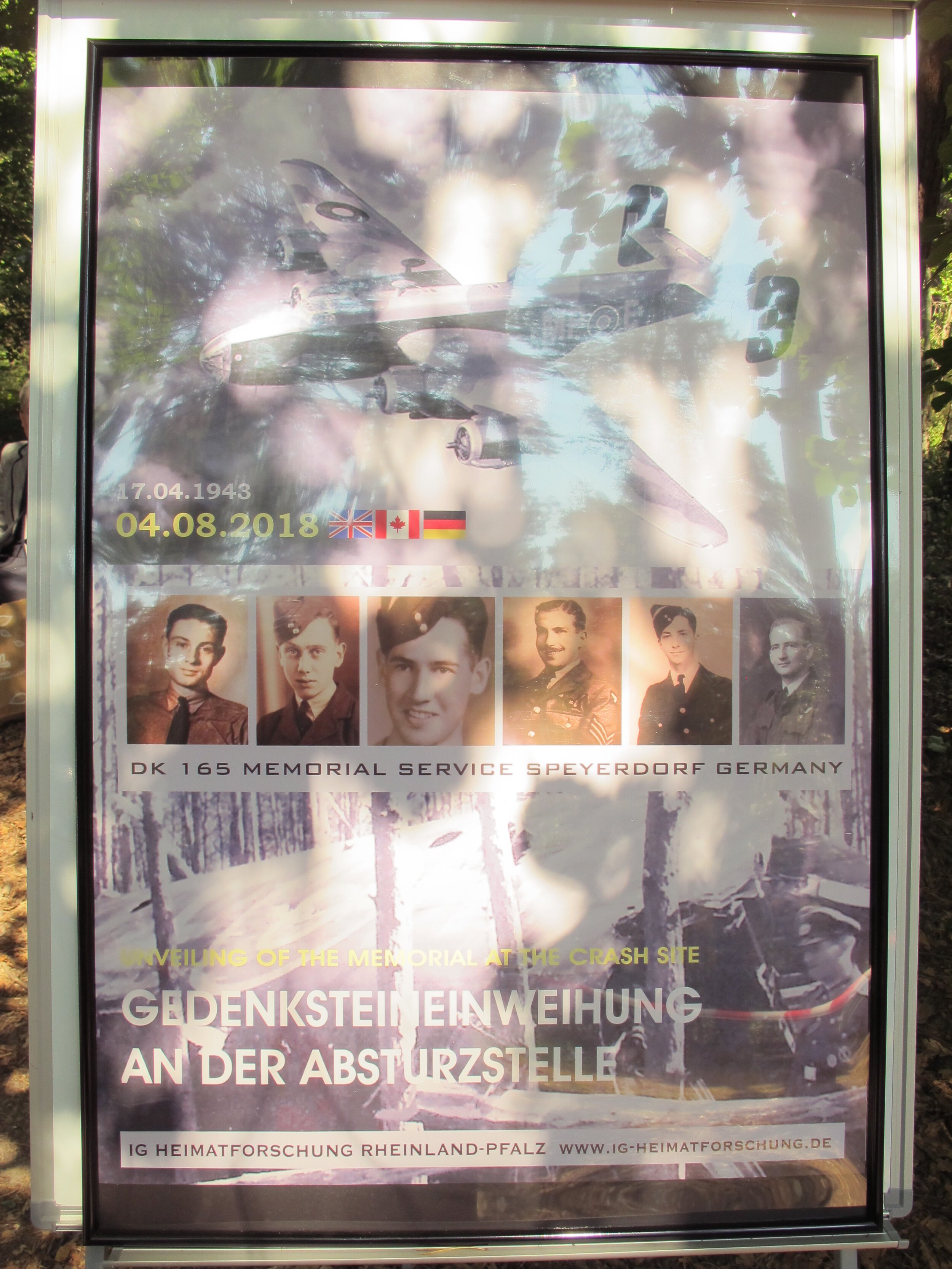

Chorley Records record that DK165 MP-E crashed between Lachen and Speyerdorf, 3 miles (5 km) SE of Neustadt. Those who died rest in Rheinberg War Cemetery.

Chorley also records an interesting note that will, I know, be helpful to those who have an eye for technical detail. The Chorley team writes:

“The Mk II Halifaxes lost from 76 Squadron were the last of this type to be reported missing from the Squadron, while the Mk V was not only the first to be lost from 76 Squadron, but is believed to have been the initial loss of its type on a bombing operation. Previous Mk V casualties had been from the Special Duty Squadrons based at RAF Tempsford. ”

“As part of the Royal Air Force Special Duty Service, the [RAF Tempsford] airfield was perhaps the most secret airfield of the Second World War. It was home to 138 (Special Duty) Squadron and 161 (Special Duty) Squadron which dropped supplies and agents into occupied Europe for the Special Operations Executive (SOE). 138 (SD) Squadron did the bulk of the supply and agent drops, while 161 (SD) Squadron had the Lysander flight, and did the insertion and pick-up operations in occupied Europe.”

I’d not heard of the Special Duty Squadrons before, so I quote here direct from the comprehensive internet records. However, a note of caution. I quote here uncited sources on Wikipedia.Wikipedia is a marvellous source, but it is imperative that we give inline citations.

Through family archiving and the love and affection I received from Sgt-Plt Ken Webb’s brothers, Desmond Budd Webb (1927-2012) our father, and Arthur Horace James Webb (1914-2006) our paternal uncle, my sisters and I have obtained a pretty good awareness of Ken’s character and personality, his daring-do, and endless sense of fun, summed up in one tiny phrase Life is Good. It tells me something, too, about the Webb Crew.

Allocation of aircraft was precise. Assessment of crews, deliberate.

I am aware of something else too, that their brother had told them on his last leave home in the Spring 1943 that the average life expectancy was four operations. And Frothblower was that fourth operation.

I grew up knowing the faces of the Webb Crew.

Sergeant Williams, Sergeant Kay, Sergeant Mitchell and Flight Sergeant Brown had all visited my grandparents’ home at 25 Windsor Street where I grew up at No. 20 across the road ten years later. Thus, I felt I knew them all.

Because Sergeant Leslie Mitchell - the mid upper gunner - mercifully survived the crash, on his repatriation he went immediately to 25 Windsor Street.

This is reported in A Shaky Do by Peter Wilson Cunliffe. Peter’s work recounts the purpose of Operation Frothblower and Operation Chubb in which he, too, lost his uncle. (A Book Review can be read on both of my websites in the book review sections).

I refer to family anecdote now, so there is an immediate note of caution. I see the phrase family anecdote and immediately imagine ancestry down the centuries passing stories on, but often accompanied by that unwelcome wayfarer, embellishment, adding or subtracting as it sees fit.

Anecdotal

DK165 MP-E was caught in searchlights over Plzeń Czechoslovakia, but successfully escaped the beam.

My father used to speak of how Jack Kay, the bomb aimer, demonstrated to him and his brother how they had once been caught in searchlights. This, too, is substantially recorded on my websites so that is for another time, other than to say that I was always struck by how Dad’s hand movements copied Jack’s movements imagining one hand as the Halifax and the other hand being the searchlight beams, and Jack’s comment ‘we’ll fly with Ken anywhere.’ It was the angle of attack that used to have my eyes popping out, as I imagined flying down a searchlight beam.

Jack, Ken Williams and Geoff Brown had all crewed with Ken Webb when they first met on Coastal Command with the ‘flying pencil’ the Armstrong Whitworth Whitley. So, in service terms, in wartime Bomber Command the four of them went back a long way.

At the war’s end, Les Mitchell went on to explain that after escaping the searchlights, they had gone on to do their bomb run, had released their load, and then turned back but knowing that by now the night-fighters would be waiting and in strength. So far as I recall, being caught in the searchlight, or coned, happened as they approached Plzeń.

German anti-aircraft batteries were highly efficient, accurate and lethal.

I make these notes not simply with DK165 in mind, but with the names (and many of the faces too) of our four crews from 76 Squadron, 28 young men, one of whom is only 17 years of age. This helps us to then comprehend the magnitude of what faced all the crews on those two operations. It was indeed A Shaky Do ~ classic RAF understatement for something that is horrifying.

Les Mitchell (known by the family as ‘Mitch’) continued… that they had been hit and were gradually losing height.

They were now well into Germany and approaching the Rheinland-Phalz. Having been to the crash site, seen the still evident clearing high up in the trees where the forward section of the Halifax came through those trees, the proximity of the former Luftwaffe air base on the edge of the wood, (the buildings still stand) I cannot help but wonder that my uncle’s navigator, Sgt Ken Williams (known by his family by his second name Rees) was, at my uncle’s request giving Ken the coordinates of clear land to attempt a landing.

I’ve discussed this with the lead archaelogist, Herr Erik Wieman, who located the crash site in 2015 and who brought about, with his team I G Heimat Forschung, the beautiful Memorial that now stands on the very spot where the cockpit finally rested. But the clear land was a fighter base. Fighter planes were dispersed in wooded clearings along the road between Lachen and Speyerdorf. From the aviator’s viewpoint, it is an incredible geographical location, the road also undoubtedly serving as an extra runway during operations. These were frantic times.

Mitch described a severe explosion at the rear, at about 10,000 feet (3,048 meters) about 25 miles (40 km) east of the eventual crash site. I suspect it might have been slightly lower height. Sgt Webb said “Les go back and see what’s happened and how Geoff is”. I’m aware of strict protocol in the RAF of World War 2, so I imagine that this would have been more formal. But relating this to my grandparents in the Autumn of 1945 in the front room at Windsor Street would have been a very different affair, especially as all were known. I’m aware, too, of the enormous pressure that Mitch would have felt. I’m always heartened, therefore, to recall his Post-War Wedding Portrait on the Wireless in the front room in the rank of Warrant Officer Class 1, and even more so, that in 2018, my sisters and I met Mitch’s Son, Steve and his Grandson, both over from Canada for the Ceremony.

The damage was very heavy. Tail-End-Charlie, Flt Sgt Brown was found, lifeless, 17 miles (27 km) away. I pause at this point to reflect upon a phrase that is part of my RAF commissioning scroll

… according to the Rules and Discipline of War

Why?

Two things.

The Webb Crew were buried with full military honours by the Luftwaffe.

Flt Sgt Brown’s remains were laid alongside five of his friends in the Lachen Speyerdorf cemetery where they rested, guarded by a young girl for four years from age 7 to age 11, Hedi from 1943 until 1947 when the six crew were laid together at the Rheinberg Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery Nordrhein-Westfalen. The German authorities had, at least at this stage, complied with the Geneva Convention and had reunited the fallen crew promptly and reported the loss through official channels, most probably via Switzerland and Sweden.

I had not realised the fate of Flt Sgt Brown until I read Peter Cunliffe’s A Shaky Do. It came as a shock. Even more so to his niece who did not learn of this until the morning of the Ceremony on Satrday 4 August 2018.

Les Mitchell went on to describe that just as he had reached the tail end of the fuselage, a huge explosion immediately beneath the mid upper turret broke the aircraft in two. The tail section with its twin fins caused it to “fall like an autumn leaf”, a phrase I’ve never forgotten since my grandmother first used it. Perhaps that explains why I love autumn leaves. My father’s mother recalled something else… Mrs Webb, had Ken not told me to go back aft and check on Geoff, I wouldn’t be here now.

Unable to free himself from the wreckage, now resting in woodland, he banged frantically on the side for help, fire being the ever present danger. Local German civilians did just that, propping him up against a tree and giving him a lighted cigarette and pointing across to where the main part of DK165 lay.

A Tribute to the Men and Women in Service at RAF Linton-on-Ouse

Saturday 3 April 1943

Halifax W7805 MP-M

Ground Crew bombing up at RAF Linton-on-Ouse Saturday, 3 April 1943

I end with a note on the black and white photograph of a Mk II Halifax being loaded up by the ground crew.

This aircraft is recorded as W7805 MP-M of 76 Squadron. This is only 13 days before Operation Frothblower and Operation Chubb, and it highlights not only some of the personnel at Linton-on-Ouse, but it gves us a very vivid idea on how things would have proceeded throughout Friday 16 April. Some will have known the crews remembered here.

The Howarth Crew

Halifax Mk II W7805 MP-M Essen Took off 19:26 Linton

Sgt J K Howarth

Sgt W C Pitt

Sgt G A Egan

Sgt J W S Blakey

P/O PW Digby MID

Sgt F G Williams

Sgt H N Richards

Chorley Records record that W7805 MP-M crashed at Hervest 2.48 miles (4km) ENE of Dorsten. Those who died are buried in the Reichswald Forest War Cemetery.

Sgt Egan, Sgt Blakey and Sgt Richards thankfully survived and were repatriated in 1945.

CREWS

Whether an aircraft is a single engine fighter or a twin engine medium or four engine heavy bomber, the Crew comprises two elements ~ Air and Ground. Without our Ground Crews, our Aircrews would never leave the ground. In 1940, Churchill spoke movingly, and rightly so, of The Few.

Those who know me know that in that hallowed phrase I do not limit it to Fighter Command.

Both Bomber Command and Coastal Command were waging a ferocious war on the continent and over the Atlantic and the North Sea even as our fighters were defending our Island whatever the cost may be. Note 4

The Chorley Bomber Command Losses (1939-1940) make for grim reading. Likewise the definitive F.K. Mason Battle Over Britain Losses first published in 1969.

Neither let us forget the pilots of the Air Transport Auxiliary. Women and men (the men prevented by age from combat), who were delivering unarmed fighters and bombers, often flying within sight of raging dogfights to RAF stations whose squadrons were engaged in battle. Our social media Gen Z cannot be expected to comprehend this. Comprehension develops as we tread the weary path of mounting years, as all of us know.

The flight engineer was the lynchpin between these two component elements ~ Air and Ground.

We often have this lofty Hollywood image of a pilot quickly signing off the log handed to him by the ground crew’s SNCO, usually a flight sergeant or warrant officer for the heavies. But the work had been done between the flight engineers and the SNCOs Groundcrew. They spoke the same language. My mother’s brother was a flight engineer with the Path Finder Force and I only wish I had known the true role of the flight engineer when my parents were alive. Having sorted things out, the engineer would call up to his skipper that their “beauty” was ready to be signed off and he would then have a final chat with the SNCO Groundcrew.

Something else, too. Groundcrews always saw their aircrews off. Aircrews were well aware that they had, for eight hours, been entrusted with a groundcrew’s personal property. But these two sentences also belie something else. The intimate bond between BOTH elements of an aircraft’s Crew.

It is for this reason that it is right to frame this with this incredible image of HM Queen Elizabeth visiting a Pathfinder squadron. Here is the Crew. As you look along the line, ground crew and air crew are intermingled. They are the Crew of the Avro Lancaster standing over them.

HM Queen Elizabeth inspects flight and ground crews of 156 Squadron at RAF Warboys, February 1944. The Avro Lancaster is also of 156 Squadron in Huntingdonshire (now Cambridgeshire)

In Conclusion

Part I

On 18/19 April 1943 newspaper headlines starkly declared that 55 aircraft had failed to return, the highest number of losses in Bomber Command in a single operation of the war to date. This meant something in the region of 385 men. But accounts differed. Some said 55 aircraft, others less.

I used to draft the estate and trust accounts for clients who had died and for whom I had often drafted their wills and trusts. One such, was a tail-end charlie, a very gentle, warm-hearted man. He spotted a small model aeroplane on my desk, learned of my own post-war service, and decided to talk a little about his wartime service. It made me realise that I had often worked with people who had served in Bomber Command. Yet, one would never have known. I think of a Chief Superintendent I served under in the 1970s. Only at his funeral in this century, did I learn that he had been a sergeant-pilot on heavies. One would never have guessed it.

One winter’s day in December, I decided to look at Operation Frothblower and Operation Chubb through the eyes of the pilots. I did not realise that I was creating for myself a template. I have since used the template from the flight engineer’s viewpoint, to obtain a better understanding about the work my mother’s brother did as a Pathfnder flight engineer on Avro Lancasters and I write elswhere of that Operation on 16-17 January 1945.

As I inputted the data, using the Chorley War Records, it was as if I was seeing the night of 16-17 April 1943 in real time.

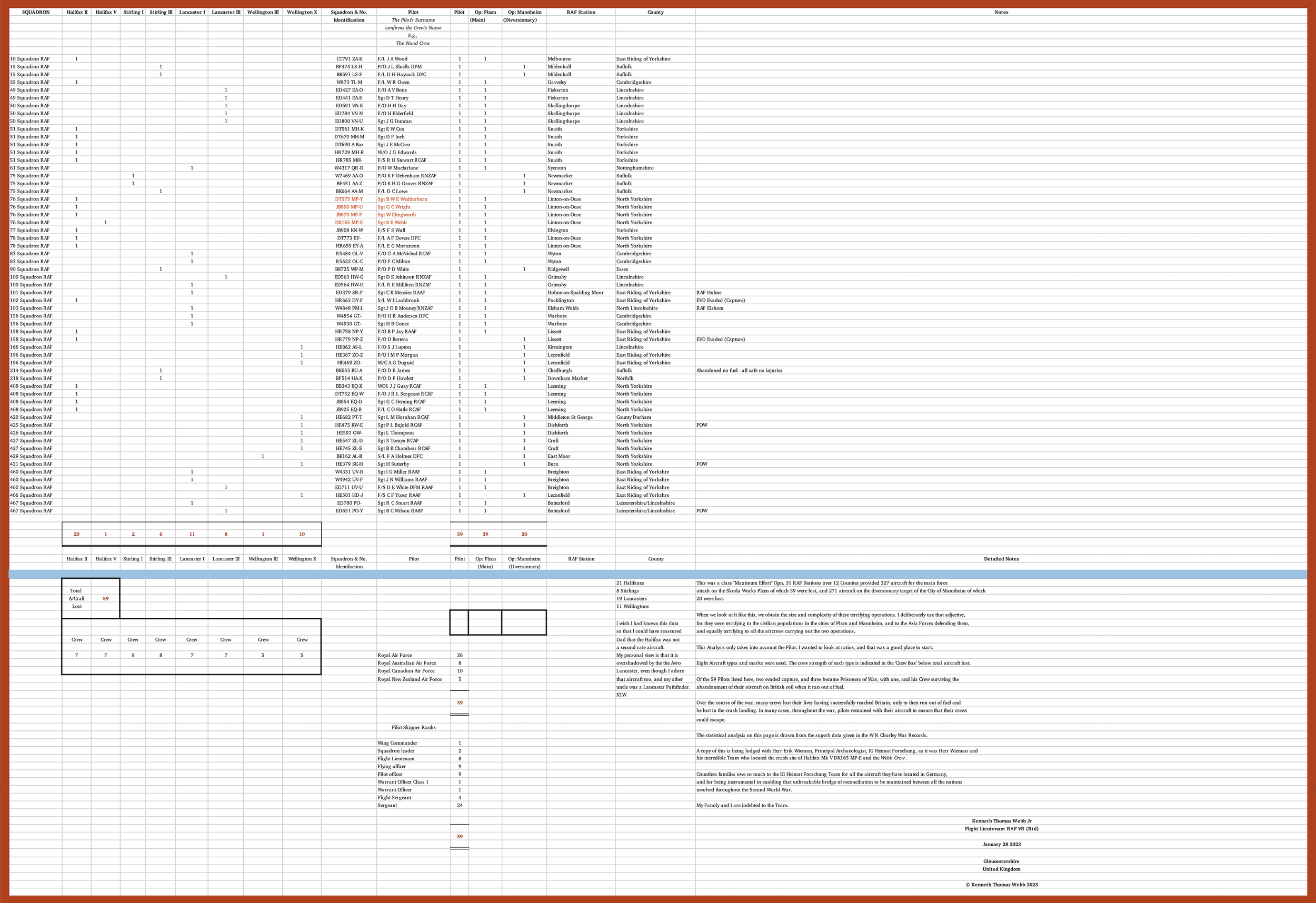

We lost 59 aircraft that night comprising:

20 Halifax II (140 men)

1 Halifax V (7 men)

2 Stirling I (16 men)

6 Stirling III (48 men)

11 Lancaster I (77 men)

8 Lancaster III (56 men)

1 Wellington III (5 men)

10 Wellington X (5 men) A total of 354 Airmen

Of these 59 aircraft, 39 were on Frothblower and 20 on Chubb.

Royal Air Force ~ 36 pilots

Royal Australian Air Force ~ 8 pilots

Royal Canadian Air Force ~ 10 pilots

Royal New Zealand Air Force ~ 5 pilots 59 Aircraft total

Pilot-Skipper Ranks 59 made up as follows:

Wing Commander 1

Squadron Leader 2

Flight Lieutenant 8

Flying Officer 9

Pilot Officer 9

Warrant Officer Class 1 1

Warrant Officer 1

Flight Sergeant 4

Sergeant 24 59 Aircraft total

At this stage of the war, on this night, of the 59 aircraft lost, 30 were SNCO pilots and 29 commissioned pilots.

The AOC-in-C Bomber Command, Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Harris was fast-tracking the commissioning of pilots to overcome the rank differential within crews.

Operation Frothblower and Operation Chubb comprised a joint “maximum effort” or Goodwood.

I remember, as a boy, hearing my parents and four grandarents speak of ‘thousand bomber raids’. In time, it was natural to assume that Plzeń-Mannheim was one such thousand bomber raid. Here is anecdote and its nuisance friend embellishment at play.

In reality, the Main Force attack on Plzeń comprized 327 aircraft, and the Diversionary Force attack on Mannheim comprized 271 aircraft.

The statistical analysis revealed something else.

This combined operation therefore committed 31 heavy bomber squadrons over 12 Counties, to assemble 598 aircraft over England and then, at precise to-the-second-timing, to head out to their respective targets in two streams.

I’ve thought long and hard about this. The Media went crazy on The Queen’s Platinum Jubilee explaining how difficult it is for the Royal Air Force to assemble the vast Fly-Past over Buckingham Palace in June 2022. Yes, of course. RAF senior officers emphasised this too. The officers interviewed on camera would be the grandchildren’s generation of that wartime adult generation. And I could only wonder at the men and women of the Royal Air Force and the Womens Auxiliary Air Force in 1939-1945. Note 5

Can today’s generation comprehend living in a world where several nights a week, many times a month, we would be assembling huge battle fleets in the air, the Royal Air Force and Commonwealth Air Forces by night, the American Army Air Force (USAAF) by day? I’m fortunate that my parents were happy to talk about the war, their brothers who did not return, and of four grandparents who were also willing to answer my endless questions. Looking back, though, as I work through the family’s archive, they very sensibly withheld much information. Thank goodness they did!

All would frequently come out with little wartime expressions. One, used by my Mum when hearing several aircraft, would produce a nod, then reminding me how it used to be, referring to listening to our aircraft assembling high above, …ah! It’s going to be a heavy one tonight! Another, and many speak of this, the engine tone of friendly aircraft and enemy aircraft. Very distinctive.

Part II

It is right that RAF 15 includes extracts from Peter Cunliffe’s A Shaky Do. In his Introduction, the author quotes Dr. Vladislav Krátkŷ of the Škoda Museum, Plzen.

“In April 1943, the Škoda workforce had reached 67,000. The core and traditional product line was guns of various calibres, ranging from 3.7 cm and higher, anti-aircraft guns 8.8 cm and heavy guns up to 21 cm. Using all the workforce available and extending the working hours to seventy-two per week, the management succeeded in boosting the works output to 2,677, guns in 1943, which represented 5.4% of the total production in German territory. The Škoda works was a major repair centre for tanks, both for the German army and their allies – Rumania (Romania) and Bulgaria. For the aircraft industry, thousands of castings for Argus, AS10, and Focke Wulf 190 engines were produced, as well as automated machine tools for the ammunition industry, submarine parts, et cetera. As Plzeñ was considered relatively safe against the ever-heavier raids, much investment activity was evident in view of expanding production, primarily of guns.”

What was thought to be the Škoda Works turned out to be a hospital. The Nazis were fast in seizing upon this. To those today who might say to me ‘how can you support this, when it is wanton atrocity?’

I would stand quietly, as I used to do when in the courtroom or earlier still when on the wide open space of an RAF Station with the keenness of the wind on my face and slicing through my uniform, that same wind that we see in the photograph of the Crew of the Avro Lancaster at RAF Warboys, and I would then say quite quietly…

I wish you to walk with me. We are going to walk across a barren landscape. It is in Ukraine, Babyn Yar just outside Kyiv. It is the 29-30 September 1941. We are about to see atrocity beyond comprehension. When we turn to leave, 35,000 civilians will have been executed, all ages, regardless of frailty. And what we have seen is the tiniest fraction of the sum total of atrocity.

We were engaged in total war. We had been forced into it by one man.

No, say nothing. No, do not ‘but’ me. I am not interested in your opinion. We have another one such man today!

A nation is doing what we did 80 years ago.

If we do not watch out, we have another man of similar mind. When War is caused by the actions and beliefs of one man or one woman, then it is for Civilisation to stand fast, stand firm.

It is for you to slip behind us in the line, you’ll be safe there. This, friend, is what I mean by the danger of total war. Never dare to compare the defence of freedom to atrocity. Never dare to suggest to me that autocracy is better than freedom and democracy and the rule of law. Never!

Now. I see you look chastened. Well, it needed to be said. Toddle off home, make yourself a stiff drink and be thankful we live in these beautiful Islands. Note 6.

Frau Hedi Kraus

Flowers have, of course, been received by Hedi this weekend on behalf of the Crew of Halifax DK165 MP-E

RAF 15 is dedicated to Sergeant Leonard Norman Jonasson RCAF of the Wedderburn Crew

who at 17 years of age

was amongst the youngest airmen

killed on operational duties with

RAF Bomber Command in World War Two.

Per Ardua Ad Astra

Flt Lt K T Webb RAF VR Rtd

Notes

A Shaky Do by Peter Wilson Cunliffe first published in 2007 Accycunliffes Publications © 2007 Peter Wilson Cunliffe ISBN 978-0-9557957-0-1

Flying Officer Tom Wingham DFC is the author of Halifax Down ~ On the Run from the Gestapo, 1944. published by Grub Sreet Publishing © Grub Street 2009 © Tom Wingham 2009 ISBN 978-1-9065023-9-3

‘shaky do’ ~ RAF understatement for an operation that is horrifying

‘whatever the cost may be’ ~ the stark reality that the prime minister, Winston Churchill, presented to the British People, to the Commnwealth and Empire, and especially so to the United States of America in 1940.

The Womens Auxiliary Air Force (WAAF) was formed in June 1939. The Womens Royal Air Force (WRAF) had been formed on 1 April 1918, disbanding in April 1920. The WAAF was formally redefined as the WRAF in 1949. On 1 April 1994 the Womens Royal Air Force and the Royal Air Force formally merged and remains today as our Royal Air Force.

Babyn Yar 1941. How the Holocaust Began by James Bulgin BBC History Magazine Issue February 2023 www.historyextra.com

DFC and DFM and MID. The Distinguished Flying Cross is a military decoration for commissioned ranks. The Distinguished Flying Medal, by no means subordinate to the DFC is a military decoration for non-commissioned ranks. Throughout the Second World War it was quite usual for a combatant to receive both. Eighty years on, for the young researcher, it informs us quietly that a person fought both as “a rank” and as “an officer”. MID affirms the honour of having been officially Mentioned in Dispatches. I merely state this to overcome the misleading information we often find in current productions when background research is not as thorough as one expects a researcher to be. The watermark of the researcher is ‘thoroughness’.

Released afresh this day 12 August 2023 in light of its popularity

16 April 2023

All Rights Reserved

LIVERPOOL

© 2023 Kenneth Thomas Webb

© 2023 Eyes to the Skies

Ken Webb is a writer and proofreader. His website, kennwebb.com, showcases his work as a writer, blogger and podcaster, resting on his successive careers as a police officer, progressing to a junior lawyer in succession and trusts as a Fellow of the Institute of Legal Executives, a retired officer with the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, and latterly, for three years, the owner and editor of two lifestyle magazines in Liverpool.

He also just handed over a successful two year chairmanship in Gloucestershire with Cheltenham Regency Probus.

Pandemic aside, he spends his time equally between his city, Liverpool, and the county of his birth, Gloucestershire.

In this fast-paced present age, proof-reading is essential. And this skill also occasionally leads to copy-editing writers’ manuscripts for submission to publishers and also student and post graduate dissertations.